Monday, August 7: Leaving Osaka Garden Palace, I walk a half mile in the pouring rain, lugging my suitcase behind me, to Shin-Osaka Station. Last night, I bought an 8:40 a.m. ticket for the Shinkansen, to arrive in Tokyo at 11:13 this morning. Since I get to the station early, I stop at Tully’s Coffee for a breakfast snack and coffee, sharing a table with a British couple traveling around Japan. We have a nice chat about our travels, and then I’m on my way.

All the way on the Shinkansen, news about the typhoon is flashing on the screen at the front of the car. I read on my phone that the worst parts of the storm are behind us, with some flooding and road closures, and I keep hoping that I’ll make it to Tokyo before the typhoon puts the brakes on the trains.

Luckily, I make it to Tokyo right on schedule, where I get on the Yamanote Line at Tokyo Station at 11:23, arriving at Nippori Station at 11:38. There, after some confusion, I take the Keisei Line for another hour to Keisei-Narita Station, where I get off and catch a taxi to my hotel, Ryokan Wakamatsu Honten. Though it’s too early to check in, I leave my bag and head out. By now, it’s about 1:40. I go in search of a restaurant for lunch, finding a nice spot where I order a sushi set meal.

sushi restaurant in Narita

sushi

The Ryokan Wakamatsu Honten is directly across the street from Narita’s biggest temple, Naritasan Shinshoji Temple.

Ryokan Wakamatsu Honten

My first piece of business is to withdraw the rest of my money from my Japan Post account, so I head down Omotesando Street in search of an ATM.

Omotesando Street

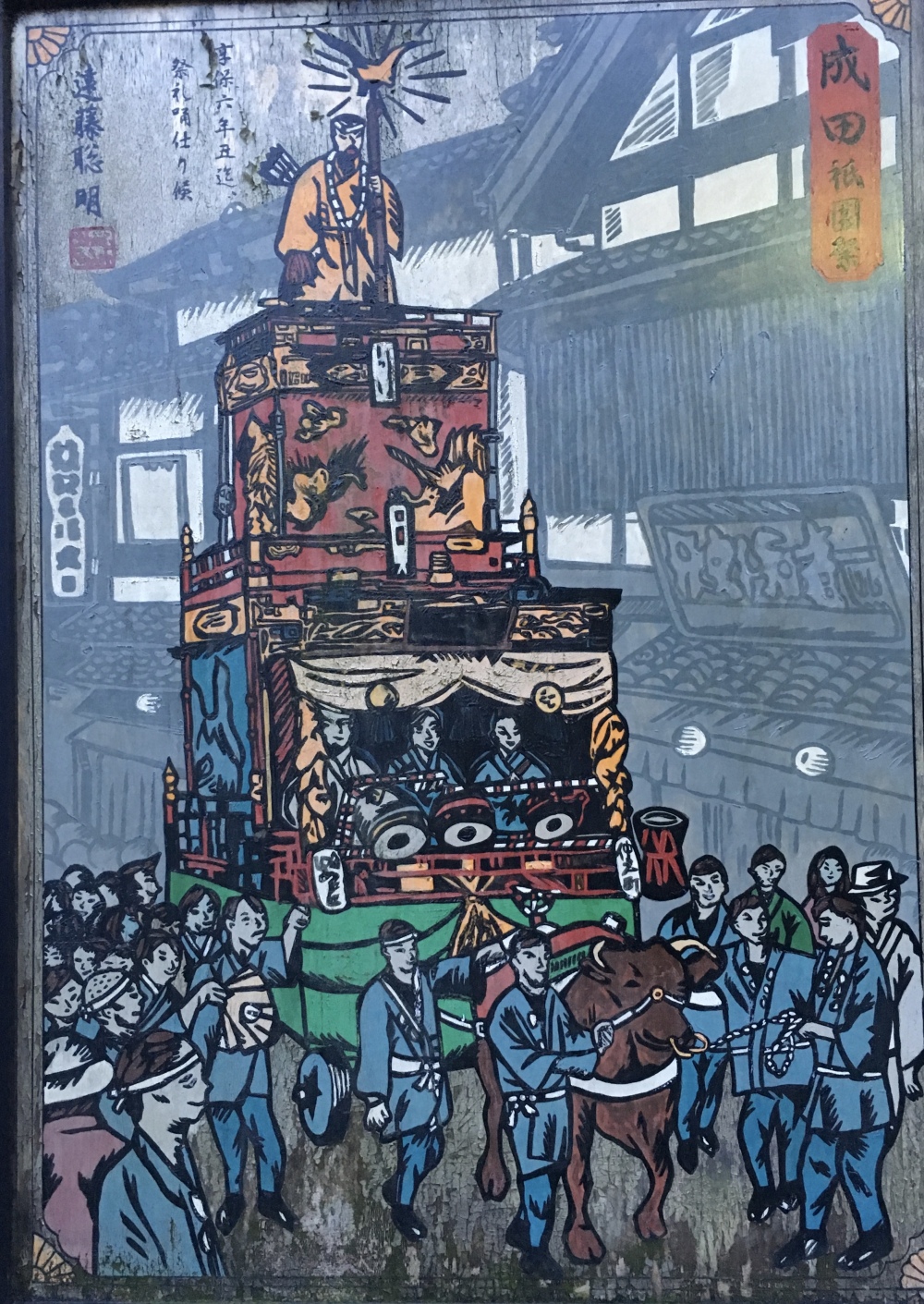

After withdrawing all remaining yen from my account, I head to Naritasan Shinshoji Temple, where I admire the impressive 2007 Somon Gate. On the upper story of this main gate, eight different Buddha images representing different birth years are enshrined to protect all people.

Naritasan Shinshoji Temple belongs to the Chisan Sect of Shingon Buddhism. The image of Fudō Myō-ō, “Unmovable Wisdom King,” the main deity of the temple, is historically significant in that Kobo Daishi (or Kukai, the founder of Shingon Buddhism) is said to have carved, consecrated and conducted a Goma ritual before this very statue in 810, by order of the 52nd emperor of Japan, Emperor Saga (786 – 842).

In 939, when a revolt led by Taira no Masakado threw the nation into chaos, the 61st emperor of Japan, Emperor Suzaku (923 – 952), secretly ordered Archbishop Kanjo, a Buddhist priest of the highest order, to carry this Fudō Myō-ō image, which had been enshrined at a temple in Kyoto, to the Kanto area battlefield to suppress the rebellion. Here at Narita, Kanjo conducted a Goma rite in front of the image lasting 21 days, praying for the sake of peace. On February 14, 940, the final day of the Goma prayer, the revolt was suppressed and Naritasan was founded to commemorate the victory.

The temple is famous for its Goma ritual, where many votive offerings are dedicated in front of the Fudō Myō-ō and special wooden Goma sticks are burnt on the altar. The fire of the Goma rite symbolizes the wisdom of Fudō Myō-ō, and the wooden Goma sticks represent the afflictions of human beings. By burning the Goma sticks, which have been inscribed with the human afflictions in the fire of Fudō Myō-ō’s wisdom, the officiating priest prays with the devotees that their afflictions might be removed (from the temple pamphlet).

Somon Gate

The 1831 Niomon Gate enshrines the four guardians of the Buddha-Misshaku-kongo on the right and the Naraen-kongo on the left in the front, and Komoku-ten and Tamon-ten in the back.

walkway to Niomon Gate

As with all Japanese temples, there is a water purification area where visitors should cleanse themselves before entering the temple grounds.

water pavilion

The huge red lantern at Niomon Gate is impressive in its size.

Niomon Gate

Lantern at Nioman Gate

Nioman Gate

lantern at Nioman Gate

straw sandals at Nioman Gate

lantern at Niomon Gate

straw sandals at Nioman Gate

Niomon Gate’s lantern is quite beautiful.

lantern at Niomon Gate

Adjacent to the Niomon Gate is Nio-ike pond, where people can release live fish symbolizing the Buddhist teaching of nonviolence, or the belief in the sacredness of all living creatures. A rock in the pond is covered with a congregation of small turtles.

Pond with turtles around Niomon Gate

around Niomon Gate

around Niomon Gate

There are many halls and buildings on the grounds of Naritasan Shinshoji Temple.

Naritasan Shinshoji Temple

Naritasan Shinshoji Temple

The 1712 Three Storied Pagoda enshrines five Buddhas, and reliefs of 16 Buddhist saints are carved on the inner wooden walls.

Three Storied Pagoda

Three Storied Pagoda

The Three Storied Pagoda here has magnificent ornamentation and vivid colors.

Three Storied Pagoda

Three Storied Pagoda

Three Storied Pagoda

The Great Main Hall, built in 1968, is where the most important Goma ritual is performed in front of the Fudō Myō-ō image, along with the Four Messengers. I’m lucky enough to attend this ritual as they hold one at 3:00. It goes for about a half hour, with the head priest and other monks chanting and throwing wooden sticks into a fire. It’s miserably hot today, so though the ritual is fascinating, it’s an uncomfortable 30 minutes.

Great Main Hall

Great Main Hall

After the Goma ritual, I go out to explore the rest of the grounds. The Shotoku-taishi-do (or Prince Shotoku Hall) was built in 1992.

Shotoku-taishi-do

Shotoku-taishi-do

ema at Shotoku-taishi-do

ema at Shotoku-taishi-do

lanterns around Shotoku-taishi-do

Prince Shotoku (572-622 AD) is considered the “Father of Japanese Buddhism.” This hall was erected with the hope of realizing world peace based on the Prince’s ideal: “Harmony should be valued among people.”

Shotoku-taishi-do

Naritasan Shinshoji Temple of course has its own unique ema.

ema at Naritasan Shinshoji Temple

ema at Naritasan Shinshoji Temple

Shaka-do Hall, built in 1858, was previously used as the main hall. Enshrined within are Sakyamuni Buddha in the center, and four bodhisattvas. The reliefs of 500 Buddhist saints and 24 paragons of Filial Piety are carved in the walls.

Shaka-do Hall

Shaka-do Hall

inside Shaka-do Hall

ema at Shaka-do Hall

Shoutendo Hall enshrines the secret Buddha statue of the temple, Daisyo Kangiten. Every first week of the month, a special prayer is performed by a priest. This hall was rebuilt in 2008 as the 1070th anniversary of the temple’s opening.

Shoutendo Hall

Naritasan Park was originally completed in 1928, and redesigned in 1998. It covers some 165,000 square meters. A large pond, waterfall, and fountain enhance the natural beauty of the park.

Naritasan Park

map of Naritasan Park

Naritasan Park

Naritasan Park

Naritasan Park

Naritasan Park

Naritasan Park

Naritasan Park

Naritasan Park

Naritasan Park

Naritasan Park

Besides a great array of tombstones in Naritasan Park, the pond has a pavilion and stone lanterns.

pavilion at Naritasan Park

Naritasan Park

Cool character at Naritasan Park

pavilion at Naritasan Park

Naritasan Park

stone lantern

pond at Naritasan Park

The Naritasan Museum of Calligraphy is on the grounds of the park, but it is closed by the time I get here.

The Naritasan Museum of Calligraphy

I continue my walk through Naritasan Park, sweating profusely in the heat and humidity.

Naritasan Park

Naritasan Park

Naritasan Park

path through Naritasan Park

The 58-meter high Great Pagoda of Peace symbolizes the teaching of Shingon Buddhism. The pagoda enshrines multiple Buddhas and has historical exhibitions about Naritasan, as well as a room for copying the Buddhist scriptures in traditional Japanese calligraphy.

The Great Pagoda of Peace

The Great Pagoda of Peace

The Great Pagoda of Peace

Pond and stone at The Great Pagoda of Peace

The Great Pagoda of Peace

The Great Pagoda of Peace

Past the Great Pagoda of Peace is a group of other halls, including Seiryu-Gongen-do Hall, originally built in 1732 as the guard of the Naritasan Shinshoji temple. This hall enshrines two guardians, Seiryu Gongen and Myoken.

Seiryu-Gongen-do Hall

Komyo-do Hall, 1701, was originally built as the Main Hall. It is a significant and colorful structure from the middle-Edo period. Enshrined here are Dainichinyorai Buddha in the center, Fudō Myō-ō on the right side, and Aizen-Myō-ō on the left side.

Komyo-do Hall

Okuno-in Cave is 11 meters deep and enshrines Dainichi Nyorai. The door is left open during the Gion Festival from 7th-8th July. One of the stone slabs affixed to the entrance bears an inscription dated 1336.

Komyo-do Hall

ema at Komyo-do Hall

at Komyo-do Hall

Okuno-in Cave

Sanja Shrine consists of three shrines, which are, from left to right, Hakusan Myojin Shrine, Konpira Daigongen Shrine and Imamiya Shrine.

Sanja Shrine

Kaizando Hall enshrines Kanjo, who founded the Naritasan Shinshoji Temple in 940. The hall was built in 1938 commemorating the 1,000th anniversary of the temple

Kaizando Hall

Gaku-do Hall (1861) displays votive tablets (votive pictures of horses and the like) dedicated by devotees. The Hall contains a large stone image of Ichikawa Danjuro VII (famous kabuki actor) and the “Giant Bronze Globe (built in 1907).”

Gaku-do Hall

Gaku-do Hall

After my long and exhaustive walk around the sprawling temple, I return to my room at Ryokan Wakamatsu Honten, where I relax after soaking in the onsen. It’s nice and cool in my room and it feels good to have the sweat washed away.

My room at Ryokan Wakamatsu Honten

phone in my room

My room at Ryokan Wakamatsu Honten

My Ryokan is directly across the street from Naritasan Temple and I have an excellent view from my window of Daishi-do Hall and Korinkaku Hall.

view from my window of Daishi-do Hall and Korinkaku Hall at Naritasan Temple

After a while, I go out to search for dinner, stopping first to take a parting shot of the Somon Gate in the blue light.

Somon Gate in blue light

Naritasan

By this time of night, the old town is quite deserted and I have to walk a long way to find an Indian restaurant where I can enjoy a meal.

Omotesando Street

Omotesando Street

Omotesando Street

Tuesday, August 8: In the morning, I take an early taxi to Narita Airport, where I have a 10:40 a.m. flight to Dallas/Fort Worth airport. However, we sit on the runway for over an hour because Alaska’s tiny Bogoslof volcano erupted, sending an ash cloud about 6 miles into the sky. As a “red” aviation warning was issued, we couldn’t take off until a new flight path was charted.

We took off over an hour late, so I knew before we left the ground that it was unlikely I would catch my connecting flight home to Virginia.

After an 11 hour and 45 minute flight, I arrive in Dallas at 9:50 a.m. on the same day, August 8, earlier than I left. I always find this amusing when traveling home from Asia.

However, because of our late departure from Tokyo, by the time I disembark from the plane in Dallas, I’ve missed the boarding time for my connecting flight. It turns out I will get on a later flight to Dulles Airport, a more convenient airport to my Virginia home than BWI, where I was originally scheduled to land.

Because I have extra time to kill in Dallas, I enjoy a Mexican lunch at the airport, as I won’t arrive home until dinnertime.

lunch in Dallas

Finally, after a three-hour and 12 minute flight, I’m back home, and my Japan adventure has come to an end.

It has been a great adventure, a whirlwind really, and I feel a bit despondent that it’s all over. 😦

Sunday, August 6: After walking through the mystical Okunoin, I stop to check in at Kumagaiji, the temple lodging, or shukubō, where I plan to spend the night. I don’t linger, since I have plenty of time this evening to explore the temple, but instead head out to finish exploring Kōyasan, making my first stop at Kongōbu-ji Temple.

In the year 804, Kobo Daishi (Kukai) crossed the sea to China to seek out Buddhist teachings. In the capital of Tang Dynasty China, he found a lineage of Buddhism, Shingon Buddhist, relatively unknown in Japan. Returning to Japan in 806, he began teaching. In 816, he was granted permission from the Imperial Court to build a monastic complex at Mt. Kōya, isolated from the distractions of the capital. Kobo Daishi lived and taught in Mt. Kōya for many years until he finally entered into eternal meditation in 835. Pilgrims flock to his mausoleum at Mt. Kōya in great numbers every year. He is believed to give aid and comfort to the millions of people who pray to him in their homes, local temples and at Okunoin.

The original temple was built in 1593 to memorialize Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s mother, some of whose hair was kept here. The temple was lost in fires two or three times and was rebuilt in 1863. Two temples, Kozanji Temple and Seiganji Temple, were combined in 1869 and renamed Kongōbu-ji Temple, meaning Temple of the Diamond Mountain Peak, to function as the headquarters of Kōyasan Shingon Buddhism. Kongōbu-ji is part of the “Sacred Sites and Pilgrimage Routes in the Kii Mountain Range” UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The gate is the oldest building at Kongōbu-ji and was constructed in 1593.

Kongobuji Temple

Kongobuji Temple

The Koya-maki (Japanese umbrella pine) was planted to celebrate the imperial visit of Emperor and Empress Showa on April 18, 1977. Koya-maki is the seal of Prince Hisahito.

Koya-maki (Japanese umbrella pine)

Koya-maki

Koya-maki at Kongobuji Temple

Kongobuji Temple

Kongobuji Temple

Kongobuji Temple

Kongōbu-ji Temple is centered around the Great Main Hall.

Kongobuji Temple

A Buddha Hall contains many sliding screen doors of cranes guessed to have been painted by Tashitsu Saito, who was active in the early Edo period.

Ohiroma

Ohiroma

Ohiroma

Out on the porch are panels of Japanese characters but I’m not sure what they are.

panels of wishes?

The temple’s modern Banryūtei rock garden is the largest rock garden in Japan (2,349 meters). The design is of a pair of dragons emerging from a sea of clouds to protect the temple. The dragons are made of 140 pieces of granite brought from Shikoku while the white sand is from Kyoto.

Banryūtei rock garden

I love looking at this amazing rock garden from every possible angle.

Banryūtei rock garden

Banryūtei rock garden

Banryūtei rock garden

Banryūtei rock garden

Banryūtei rock garden

Banryūtei rock garden

Banryūtei rock garden

Banryūtei rock garden

Banryūtei rock garden

Banryūtei rock garden

Banryūtei rock garden

Inside, I find more panels of crane paintings.

painted panels

Kongobuiji Temple

Visitors can get a glimpse of the Mausoleum of Bishop Shinzen, originally built in 1640 to honor Shinzen, the disciple and successor of Kobo Daishi. He worked as a manager of Koyasan for 56 years. A small altar is set up in front, and the building is roofed in the traditional way with cypress bark. Repairs were completed in October, 1989 in preparation for the 1100th anniversary of Shinzen’s death. During the repairs, a relic container was discovered. The building was consequently renamed the Mausoleum of Shinzen and rededicated.

The Mausoleum of Bishop Shinzen

After leaving, I wander along the main road, passing once again past the beautiful grounds of Shojoshin-in, another shukubō.

Shojoshin-in

Shojoshin-in

Shojoshin-in

The garden of Hōzen-in Monastery was here in the early Momoyama Period (1573-1615). The stones are arranged to symbolize the landscape. The waterless waterfall is an unusual feature.

Hōzen-in Monastery

The garden of Hōzen-in Monastery

The garden of Hōzen-in Monastery

The garden of Hōzen-in Monastery

Ekōin is another temple lodging with pretty grounds.

Ekōin

Ekōin

Ekōin

Karukayado Temple tells the story of Karukaya-Doshin and Ishidomaru in panels spread around the inside perimeter. You can read some of the story here.

Karukaya-Doshin and Ishidomaru

Karukaya-Doshin and Ishidomaru

The first panel depicts the feudal lord, Kato-Hyuoenojo-Shigemase, who lived in modern Fukuoka prefecture over 800 years ago. He had no children, so he prayed at Kashii-no-miya shrine. As a result, he was blessed with a child. When the child grew up, he was named Kato-Saemon-Shigeuji and was later given the name Karukaya-Doshin.

the feudal lord prays for a child

The rest of the story of Karukaya-Doshin and Ishidomaru encircles the temple in panels, with the story written in both Japanese and English.

story of Karukaya-Doshin and Ishidomaru

story of Karukaya-Doshin and Ishidomaru

story of Karukaya-Doshin and Ishidomaru

story of Karukaya-Doshin and Ishidomaru

story of Karukaya-Doshin and Ishidomaru

story of Karukaya-Doshin and Ishidomaru

I continue walking down the main road and climb steps under a series of torii gates to explore Kiyotaka Inari Shrine.

Kiyotaka Inari Shrine

Kiyotaka Inari Shrine

Kiyotaka Inari Shrine

A small family seems to be in charge of this shrine. The father and son point to the cedar trees that meet and grow together near their tops.

cedars growing together at Kiyotaka Inari Shrine

guardian dog

Kiyotaka Inari Shrine

Kiyotaka Inari Shrine

The boy offers me a cup of tea and a snack, which I enjoy as I haven’t yet had lunch and it’s near 2:30.

tea, snack and origami

boy at Kiyotaka Inari Shrine

As I continue my walk down the street, I find a contemplative monk clopping down the sidewalk in wooden sandals.

a monk walks by a Koyasan temple

a monk in motion

Koyasan temple

I find a late lunch in a small unpretentious cafe.

lunchtime cafe

lunchtime

At 3:10, I’m tired and hot from all my walking. So I go to Kumagaiji, my temple lodging for tonight, and simply walk around the temple and the grounds for a short time.

Kumagaiji

Kumagaiji

Kumagaiji

Kumagaiji

Kumagaiji

ema at Kumagaiji

ema at Kumagaiji

Kumagaiji

Kumagaiji

The grounds of Kumagaiji have the typical Japanese garden with a pond and stone lanterns.

Kumagaiji grounds

Kumagaiji grounds

Kumagaiji grounds

Kumagaiji grounds

Finally, I lie down on my futon in my small tatami-matted room with a fan blowing directly on me. Last night, at Kongo Sanmaiin, the temple was air-conditioned, but this one is not, and it’s quite miserable. The fan just doesn’t work to cool me off, but I try to take a short nap anyway.

The Kumagaiji guests sit down for dinner at 5:30.

dinner at Kumagaiji

The dinner is quite similar to the one I had last night at Kongo Sanmaiin, but it isn’t quite as good. Maybe because of the heat…

dinner at Kumagaiji

my seating assignment

dinner at Kumagaiji

In the middle of our dinner at Kumagaiji, a Japanese lady from the temple’s staff alarms us with news that a typhoon is coming overnight. She warns that the typhoon might shut down the cable car and thus not be able to take us down the mountain in the morning. As I have a 7-hour trip from Koyasan to Narita planned for tomorrow, and an early flight back to the U.S. on Tuesday morning, I am worried that I might not make it to Narita tomorrow. After debating with myself in my sweltering room for a half-hour after dinner, I quickly make a reservation at Osaka Garden Palace, pack up my bag and check out of the temple lodging, losing the 12,000 yen (~$110) I already paid. I catch a bus to Koyasan Station, where I catch the 7:50 p.m. cable car to Gokurakabashi Station. The cable car is deserted except for a Spanish guy and a Japanese girl, both of whom speak a little English and take me under their wings. They are also headed to Osaka, so we decide to stick together.

We catch the 7:59 Nankai-Koya Line to Hashimoto Station, arriving at 8:46, and then stay on the line to Namba Station.

This is what the Nankai-Koya train line to Namba Station looks like at 9:14 p.m., nearly deserted. We arrive almost an hour after leaving Hashimoto Station, at 9:35.

on the Nankai-Koya Line to Namba Station

At Namba Station, I have six minutes before I must catch the Midosuji Line to Shin-Osaka, so I jump off the train and use the bathroom; luckily there’s a toilet right at the end of the platform. I make it back to the train on time, but as I get back on a different car, I lose sight of the Spanish guy and Japanese girl. They had offered to get off with me, but I told them not to worry, I’d be fine on my own.

At 9:57 p.m., I arrive at Shin-Osaka Station, where I buy a Shinkansen ticket for 8:40 a.m. Monday morning to Tokyo. I know I will need to get an early start because the typhoon is expected to hit the Kansei area in late morning. I’ve heard that even the Shinkansen might stop running in typhoon weather. I can’t abide any delays because I certainly don’t want to miss my flight home on Tuesday morning.

I have a Google Map on my phone showing me how to get from Shin-Osaka Station to the Osaka Garden Palace. It looks like about a half-mile walk. It isn’t easy to find. It takes me an hour, lugging my suitcase through a mostly residential and quite deserted area of Osaka, to find the hotel. I finally happen upon two women taking a walk, one of whom luckily speaks a little English, and points me in the direction of the hotel. I finally arrive at 11:00 p.m. exhausted and annoyed that I have to spend another 7,000 yen (~$64) for lodging, when I already paid for the night at Kumagaiji.

So much for my relaxing temple stay, and the cold beer that enticed me from the temple’s vending machine!

Steps today: 23,485 (9.95 miles). Whew! What a day. 🙂

Sunday, August 6: Early this morning, I participate in a Buddhist ceremony at Kongo Sanmai-in, the temple where I spent the night. Kongo Sanmai-in is one of Kōyasan’s 52 shukubo, temples that historically offered overnight lodging to pilgrims, but today offer accommodation to non-pilgrim tourists as well. Both Japanese and Western visitors participate in this morning’s service, although the entire ceremony of prayer, guided meditation, chanting, and even the sermon, are in Japanese. Even without understanding a word, the service is gorgeously moving, with gongs and chants and incense swirls transporting us to an otherworldly realm. At one point during the service, participants are invited to walk up and put a flower bud in a bowl, offering silent prayers. At another point, the monks lead us in a slow procession through a passageway that circles the main altar of the temple. We listen to the head monk give a long talk in Japanese, maybe 30 minutes; his words elicit a lot of laughs from the Japanese visitors. Someone tells me later that he was talking about the exorbitant costs of renovating the temples and pagodas.

Sadly, I have to check out of Kongo Sanmai-in this morning because they are booked for the second of my two night stay. I have to move a block or so up the main road to Kumagaiji, another temple where I’ll stay the night. Sadly, I find this temple is not air-conditioned, as was Kongo Sanmai-in. The room is sweltering, as is the entire temple. It’s no problem during the day, as I’ll be out and about, but at night, it won’t be pleasant.

My goal today is explore the rest of Kōyasan, especially the atmospheric cemetery of Okunoin, one of the most sacred places in Japan and a popular pilgrimage spot, as well as Kongobuji Temple. Tomorrow morning, Monday, I have a 7+ hour trip from Kōyasan to Narita, where I’ll spend the night before my Tuesday flight back to Virginia.

After leaving my bag at Kumagaiji, I walk along the main road, passing by several temples along the way. First, I walk by Daien-in, a shapely building with a Japanese cypress bark roof. The outer gate and entrance are carved with Japanese bush warblers, plum trees, and the twelve animals of the Chinese zodiac.

Daien-in

A bit further down the road, I drop into the Manihouto Pagoda at Jofukuin Temple. Here, a cheery monk is manning a welcome window, although he doesn’t speak much English. He does manage to tell me the pagoda is meant to honor those who died in WWII.

Manihouto Pagoda at Jofukuin Temple

inside Manihouto Pagoda

inside Manihouto Pagoda

inside Manihouto Pagoda

inside Manihouto Pagoda

inside Manihouto Pagoda

inside Manihouto Pagoda

The monk inside Manihouto Pagoda writes something on an all-Japanese pamphlet and I am hopeful it contains some kind of fortune for me. I later find out it’s just the name of the temple, or something having to do with the temple.

a monk inside Manihouto Pagoda

The monk demonstrates that I should pull the wooden beads, shown below, very gently, beginning with my left hand, then right, then left. I am to reach for the next bead with my eyes closed and whichever one I touch tells my fortune. Directly in front of me is a sign telling the meaning of each symbol. When I touch the bead with the yellow star, the monk gives me an exuberant hug. He points to the sign, which says the star = Great blessing. Other symbols are lesser blessings. What a lucky soul I am sometimes. 🙂

pull the cord for a fortune

symbol meanings

I leave the beautiful Manihouto Pagoda and continue up the road toward Okunoin.

Manihouto Pagoda at Jofukuin Temple

I pass by Sekishoin. Founded 1100 years ago, it is now a shukubo.

Sekishoin

Sekishoin

I also pass Shojoshin-in, another shukubo with beautiful grounds.

Shojoshin-in

Okunoin, the focal point of religious faith in Kōyasan, is an atmospheric ancient cemetery that holds more than 200,000 tombs of departed people of all classes, from common townsfolk to military commanders. The cemetery sprawls out along a 2km path through several-hundred-year-old towering cedar trees.

Most importantly, Okunoin is the site of the mausoleum of Kobo Daishi, also known as Kukai (774-835), the founder of Shingon Buddhism and one of the most revered persons in the religious history of Japan. Kobo Daishi is not considered to have died but is believed to rest in eternal meditation as he awaits Miroku Nyorai (Maihreya), the Buddha of the Future; he provides relief to those who ask for salvation in the meantime (japan-guide.com: Okunoin). Many people, including prominent monks and feudal lords, have had their tombstones built here over the centuries in hopes of being close to Kobo Daishi in death so they can receive salvation.

I pass the water pavilion near the entrance of Okunoin, and then I’m on my way across Ichinohashi bridge.

Water pavilion at Okunoin

The Ichinohashi Bridge (first bridge) marks the traditional entrance to Okunoin. It is said that Kobo Daishi comes here to greet visitors and sees them off here. Pilgrims bow here before crossing the bridge.

Ichinohashi bridge

I stroll through the mystical Okunoin for an hour and a half, mesmerized by the moss-covered tombs and lanterns, the brightly bibbed Jizo statues, and the soaring cedars. Though it seems the cemetery might be cool in the shade from those cedars, they don’t help in today’s heat, nearly 95F degrees and oppressively humid.

I keep following the paved pathway through Okunoin, mindful of the history and holiness here.

path in Okunoin

Jizo at Okunoin

Okunoin

Okunoin

Okunoin

Okunoin

Jizo at Okunoin

Okunoin

Okunoin

Okunoin

Okunoin

Okunoin is overwhelming in its majesty and its serenity. Luckily, I got here early enough that the crowds are somewhat thin this morning.

Okunoin

Okunoin

cedar trees at Okunoin

Jizo in a tree trunk

Okunoin

soaring cedars

I come upon the Graves of Takeda Shingen and Takeda Katsuyori. On the left is a memorial to Takeda Shingen (1521-1573), an important feudal lord, and on the right is that of his son, Katsuyori (1546-1582). Both monuments have the dates of their deaths on the back.

Graves of Takeda Shingen and Takeda Katsuyori

Okunoin

Okunoin

Okunoin

Okunoin

Okunoin

Okunoin

Okunoin seems to go on and on to eternity.

pathway through Okunoin

Okunoin

The black stone statue of Asekaki Jizo (Sweating Jizo), is believed to be always perspiring since it deliberately suffers all sorts of pains on behalf of people because of their wrongdoings. I can’t see the Jizo statue, hidden as it is inside this pavilion. The Mirror Well, also not pictured because I can’t find it, is supposedly adjacent to this statue. According to legend, anyone whose reflection does not appear on the well water is destined to die within three years. Maybe it’s a good thing I don’t find it.

Asekaki Jizo (Sweating Jizo)

Jizo figure at Okunoin

tangled roots of cedars

One of the two pictures below (I’m not sure which) is the Memorial for both Friend and Foe During the Invasion of Korea. This memorial stone was erected to pray for the repose of those killed on both sides during the sixteenth-century Japanese invasion of Korea (1592-1598). It was ordered by Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-1598), and built by Shimazu Yoshihiro (1535-1619) and his son Tadatsune (1576-1638) in 1599. The memorial stands within the grave area of the Shimazu family, the lords of Satsuma.

Invasion for both Friend and Foe During the Invasion of Korea

Invasion for both Friend and Foe During the Invasion of Korea

There are both jolly and imposing figures in Okunoin, but I can’t begin to know the significance of them all.

Okunoin

Okunoin

Okunoin

Okunoin

Okunoin

Okunoin

Gokusho Offering Hall lies near a row of statues depicting Jizo, a popular Bodhisattva that looks after children, travelers, and the souls of the deceased.

Visitors make offerings and throw water at the statues, known as Mizumuke Jizo (Water Covered Jizo) to pray for departed family members.

washing the Buddhas

wet Buddhas

Okunoin

Busy washing of the Jizos

The Gobyo-bashi Bridge leads visitors to the mausoleum. Before crossing the bridge and entering the “sanctuary,” it is customary for visitors to groom themselves and bow deeply to Kukai, who is believed to be still alive in the mausoleum and offering prayers for all people in the world.

The bridge, originally a wooden structure, has been rebuilt in stone. The bridge has 36 stone planks, and including the bridge itself, the entire structure represents the Buddhist deities of the Diamond World Mandala. A Sanskrit letter representing each deity is carved on the underside of each plank (japan-guide.com: Okunoin Temple).

Sadly, it’s too crowded to get a photo of the bridge without people on it.

Gobyo-bashi Bridge

Gobyo-bashi Bridge

In the stream to the left of the bridge are a group of wooden markers serving as a memorial to unborn children.

in the river

No photography is allowed once we cross the bridge, but the mausoleum is quite beautiful.

Okunoin’s main hall for worship, Torodo Hall (Hall of Lamps), is built in front of Kobo Daishi’s mausoleum. Inside the hall are more than 10,000 lanterns, donated by worshipers, which are kept eternally lit. In the hall’s basement are 50,000 tiny statues donated to Okunoin in 1984, on the 1150th anniversary of Kobo Daishi’s entrance into eternal meditation.

Behind Torodo Hall is Kobo Daishi’s Mausoleum (Gobyo), the site of his eternal meditation. Visitors come from all over to pray to Kobo Daishi, and it is not uncommon to see pilgrims chanting sutras here (japan-guide.com: Okunoin Temple).

I exit the cemetery at the second entrance to Okunoin, near the Okunoin-mae bus stop. On my way out, I pass a pyramidal mound of Jizo statues.

pyramid of Jizos

pyramid of Jizos

Jizo at Okunoin

It’s now about 11:00 a.m., and I stay on the bus until I reach the entrance of Kongobuji Temple, the head temple of more than 4,000 temples of the Shingon sect of Buddhism in the world.

Saturday, August 5: This morning, I leave Nara for the convoluted three-hour journey to Mount Kōya. I take the Yamatoji Line from Nara Station, and at Tennoji Station I change to the Osaka Loop Line to Shin-Imamiya Station, where I take the Nankai-Koya line to Hashimoto Station, about a 45-minute ride. From Hashimoto, I stay on the same line for another 50 minutes to Gokurakubashi Station, where I take the Nankai Koyasan Cable Car up to Mount Kōya. It’s only a 5 minute ride up the cable car.

Below are some views as we climb the mountain.

view from the cable car

view from the cable car

route from Nara to Mount Koya

The sacred mountain of Kōyasan wears a mantle of mystery and holiness. Situated south of the Kinokawa River in Wakayama Prefecture, Kōyasan sits in a basin on a mountain 820 meters above sea level. Kūkai (774-835), a Japanese Buddhist monk posthumously known as Kōbō-Daishi, sent his disciples to explore Kōyasan beginning in 816. It was granted to Kūkai as a place of meditation by the Imperial Court 1,200 years ago. Kūkai was also a civil servant, scholar, poet and artist who founded the Shingon, or “True Word” school of Buddhism. Practitioners at Kōyasan try to identify themselves with the Buddha by spiritual unification.

Ever since the monastic center was formed, Kōyasan has been a holy pilgrimage destination, and also home to unique cultural assets. In 2004, UNESCO designated Mt. Kōya, along with two other locations on the Kii Peninsula, Yoshino and Omine, as well as Kumano Sanzan, as World Heritage Sites: “Sacred Sites and Pilgrimage Routes in the Kii Mountain Range.”

From Kōyasan Station, I must take a bus to Kongo Sanmai-in, where I’ll be staying overnight in a Buddhist temple. Upon my arrival at the temple lodging, I find it’s too early to check in, so I leave my bags with an elderly monk at the front gate and go out to explore Kōyasan. As it’s nearly 1:00, my first order of business is to find lunch, but I find long lines at the few lunch places available. I finally find a restaurant that has some space, and I sit at the counter and enjoy my g0-t0 lunch in Japan, a tempura prawn set meal.

lunch restaurant in Koyasan

shrimp tempura – my go to meal in Japan

After I finish lunch, I go out back to a small outdoor waiting area to use the toilet. There are four available toilets, but only one is Western, so I opt to wait behind four little Japanese girls for the one Western toilet. I find it funny that even the Japanese girls don’t want to use the Japanese squat toilets, but opt to wait for the one Western one. I have to say, I get a little annoyed by this, as the girls take their sweet time to move along.

I walk some distance to Danjo Garan, also known as Dai (Great) Garan, the central temple complex of Mount Kōya. Shingon Buddhism training has been taking place here from the 9th century to the present day.

on the way to Dai Garan

a gate on the way to DAi Garan

I pass a red bridge over a lotus pond that echoes a Monet painting. The Lotus Pond is the largest pond on Kōyasan, and goes back as far as the Heian period (794 to 1185). Originally known as the Kondo pond, it was named the Lotus Pond because of the lotuses growing here. Until the first quarter of the twentieth century, the surface of the lake was entirely covered with lotuses, but because of repairs and construction, the pond’s ecology changed. Hardly any lotuses remain today.

bridge over lotus pond

One gate to the Danjo Garan is called the Chumon, or Middle Gate. The original construction of the Chumon dates back to the founding of Kōyasan. Originally, there was a torii-shaped gate here. After repeated fires and reconstructions, it was rebuilt as a two-story gate with five bays. During the Edo period (1603 – 1868), it is known to have been destroyed by fire three times, and the foundation stones from the before the fires are buried underground.

Chumon, or Middle Gate

The Chumon burned down in 1843 and was not rebuilt for 172 years. Only the foundation stones were exposed at the site until it was reconstructed to commemorate the 1200th anniversary of the founding of Kōyasan in 2015. The images of Dhritarashtra and Vaisravana in the font of the gate date from the reconstruction of 1820.

Guardian King of the Chumon

Guardian King of the Chumon

The Kondo, or main hall, was central to Kūkai’s vision for an esoteric Buddhist monastery secluded in the mountains, flanked by stupas (pagodas) to the hall’s east and west. Though construction began in 819, it wasn’t finished until after Kōbō-Daishi entered eternal meditation in 835. Many rituals and ceremonies are held here.

Kondo, or main hall

Kondo, or main hall

Kondo, or main hall

back side of Chumon

Details of the Kondo

The Kondo enshrines a statue of the Medicine Buddha that is not displayed, flanked by two large hanging mandalas, each with its own separate altar. Wall paintings show the eight offering bodhisattvas in the corners, and a large mural of the Buddha’s enlightenment is on the north side of the Kondo.

inside the Kondo

inside the Kondo

Inside the Kondo are wall paintings and murals.

murals inside the Kondo

murals

murals

The hexagonal shaped Rokkaku Kyozo was built in 1159 to house a complete copy of the Buddhist scriptures, written in gold ink. The building was lost in the fire of 1843, was rebuilt in 1884, and was lost again in the fire that destroyed the Kondo in 1926. The existing building was rebuilt in 1934. The 1884 building could be revolved, but only the present building’s outer rim can be revolved.

Rokkaku Kyozo

Konpon Daito, or the Great Fundamental Pagoda, is the tallest building in Kōyasan. After Kūkai was granted the use of Kōyasan by Emperor Saga in 816, he decided to build the first monastic complex entirely dedicated to the teaching practice of Esoteric Buddhism. He planned to construct two large two-story pagodas diagonally behind the Kondo in the eastern and western directions. Plans called for the Konpon Daito to be about 48.5 meters high, and because of its great size it was finally completed in 876, about 40 years after Kōbō-Daishi entered eternal meditation.

Konpon Daito, the stupa on the east side of the Kondo

Shoro Belfry at Dai Garan

In later centuries the Konpon Daito was destroyed in fires caused by lightning strikes five times, and rebuilt each time. After the great fire of 1843, only the foundation stones remained. The existing building was rebuilt in 1937 of ferro-concrete with wooden overlays painted in vermilion because of the long history of fires. The building was last renovated in 1996.

The body of the pagoda is circular, with a square lower story with an attached pent roof and walls. The majestic Konpon Daito has the exact dimensions today was when it was first built. It enshrines a three-dimensional mandala, with large gilt wooden statues of Dainichi Myorai (Mahavairocana) of the Taizokai (Matrix Realm) surrounded by the Four Buddhas of the Kongokai (Diamond Realm), with the Sixteen Great Bodhisattvas painted on the sixteen pillars around them. Sadly no photography is permitted.

Konpon Daito is known as a symbol of Kōyasan.

Konpon Daito

hall at Dai Garan

The Tōtō (Eastern Stupa) was completed in 1127 at the wish of the retired Emperor Shirakawa. The main deity enshrined is Vikiranosnisa, who is flanked by two wrathful deities. The pagoda that had been rebuilt in the Edo period burned to the ground in 1843, and the present building was reconstructed some 140 years later, in 1983.

Tōtō (Eastern Stupa)

Tōtō (Eastern Stupa)

Konpon Daito

Konpon Daito

bronze lantern and Kondo

a monk walks by the bronze lantern

hall at Dai Garan

pavilion at Dai Garan

Myō-jinja is home to Niu-myōjin, the royal mistress of Mount Kōya, and her son Kariba-myōjin, hunter guardian of the mountain’s forests. Most of Dai Garan is shaded by soaring black cedar trees.

torii at entrance to Myō-jinja

Sannoin

The Saito, or Western Stupa, was originally built in 887, according to the instructions of Kōbō-Daishi. The present structure is the fifth reconstruction of the original building, and was built in 1834. The 36 pillars inside, plus the central pillar, represent the 37 deities of the Kongokai Mandala. Five Buddhas are enshrined here, with the central Buddha being Mahavairocana of the Kongokai surrounded by four Buddhas of the Taizokai. This demonstrates the teaching of the non-duality of the two mandalas.

I always love the older buildings that haven’t been rebuilt in ferro-concrete, like this one, although I know fires have destroyed these wooden buildings many times.

The Saito, or Western Stupa

The Saito, or Western Stupa

tree roots at Dai Garan

Konpon Daito

I wander over the red bridge to the islet in the center of the Lotus Pond.

bridge over lotus pond

On the small islet is the Zennyo Ryuo Shrine, which enshrines a queen of the Naga, or dragon gods, believed to be most powerful in answering prayers relating to water and rain. This shrine originated when a monk prayed to the queen for rain during the drought of 1771.

Zennyo Ryuo Shrine

Situated at the west end of the basin of Koyasan, the Daimon, or Grand Gateway, is the western entrance to Koyasan from Kinokawa Valley and Aritagawa Valley. The gateway was reconstructed in 1705. It was recently repaired when the motorway opened.

The Daimon, or large entrance gate, to Dai Garan

The Daimon

Inside the two main pillars of the gates are fierce looking Niō statues, guardians of this sacred area.

Niō statue

Niō statue

Temple Stay at Kongo Sanmai-in

After exploring all around Dai Garan, I walk back to Kongo Sanmai-in, where I can check in for the night.

Temple lodgings, or shukubō, are Buddhist temples that offer overnight accommodation to pilgrims and tourists. Open to both practitioners and non-practitioners, shukubō offer travelers a chance to experience the austere lifestyle of Buddhist monks while staying in historic temple buildings. In addition, visitors are usually invited to watch or participate in activities such as morning prayers or meditation (Japan-guide.com: Temple Lodgings). Of 117 temples on Koyasan, 52 of them offer lodging for overnight guests.

Kongo Sanmai-in is also considered a ryokan, or traditional Japanese inn. It has a bathhouse, multi-course dinners, communal spaces where guests can relax, and rooms with woven-straw flooring and futon mats.

The temple was built in the year 1223 by a widow named Hojo Masako, wife of the feudal lord Minamoto Yoritomo. She is said to have been the most powerful woman in Japanese history. Madam Masako became nun Nyojitsu after her husband died. She protected Kongo Sanmai-in Monastery by appointing a head priest, donating manors to the monastery, and encouraging Buddhist learning by establishing a school for learning. Yasumori, her vassal, supplied the priests with scriptures and commentaries on wooden block printing.

Kongo Sanmai-in is one of the most expensive places I stay during my time in Japan. It costs me 14,540 yen, or ~ $134. Dinner and breakfast are provided, and we are able to participate in the morning Buddhist ceremony. I have a small tatami-matted room to myself with a private bathroom. The whole experience is well worth the price.

Kongo Sanmai-in

After I settle into my air-conditioned room with private bath, I walk around to explore the grounds before dinner. I find the beautiful two-story Hato tower, dating to the 13th century.

stupa at Kongo Sanmaiin

stupa at Kongo Sanmaiin

a peek through the hydrangeas

stupa at Kongo Sanmaiin

on the grounds of Kongo Sanmaiin

Kongo Sanmaiin

The black cedar trees at Kongo Sanmai-in are ancient and majestic.

cedar trees at Kongo Sanmaiin

cedar trees at Kongo Sanmaiin

The Shisha Myojin Honden Shrine, a Shinto shrine housing the tutelary deity of Kongo Sanmai-in Temple, is inscribed with the date 1552.

Kongo Sanmaiin Temple Shisha Myojin Honden Shrine

Kongo Sanmaiin Temple Shisha Myojin Honden Shrine

path uphill

Like the stupa, this scripture repository building was also built in the Kamakura period. It is a rare example of the traditional azekurazukuri style, a simple wooden construction used in buildings like storehouses (kura), granaries, and other utilitarian structures. It is characterized by joined-log structures of triangular cross-section, and is commonly built of cypress timbers.

scripture repository

scripture repository

rakan at Kongo Sanmaiin

Kongo Sanmaiin

the grounds of Kongo Sanmaiin

Kongo Sanmaiin

I walk through the polished wooden halls of Kongo Sanmai-in and then through the interior courtyard garden. This is truly a comfortable and serene temple for a temple stay!

inside Kongo Sanmaiin

painted screen at Kongo Sanmaiin

garden at Kongo Sanmaiin

garden at Kongo Sanmaiin

garden at Kongo Sanmaiin

garden at Kongo Sanmaiin

Kongo Sanmaiin

garden at Kongo Sanmaiin

another courtyard at Kongo Sanmaiin

I finish walking the grounds of Kongo Sanmai-in.

Kongo Sanmaiin

flower pots on the steps of Kongo Sanmaiin

pagoda at Kongo Sanmaiin

pagoda at Kongo Sanmaiin

pagoda at Kongo Sanmaiin

After my stroll around the grounds, I buy a beer from a vending machine and relax in my room while waiting for dinner. I had been wondering if alcoholic beverages would be served in a temple, so I’m pleasantly surprised to find several vending machines offering an array of choices.

At dinnertime, I join the other guests in a communal tatami matted room, where we’re served a Buddhist vegetarian meal or shojin-ryori. I enjoy tempura vegetables, miso soup, seaweed, beans, steamed vegetables, hot noodles, tofu, rice and mushrooms, all artistically presented. For dessert, watermelon and kiwi.

vegetarian meal at Kongo Sanmaiin

After dinner, I take an evening walk in Koyasan. The streets are pretty deserted at this hour.

temple in Koyasan

holy figure

holy figure

pagoda in Koyasan

elephant at the pagoda

lantern and deserted streets of Koyasan

hydrangeas on the walk

sunset at Koyasan

Later, I enjoy the communal onsen, or Japanese bath, and then go to sleep early. In the morning, I’ll awake before daybreak to attend the Buddhist Sunday morning ceremony.

Total steps today: 14,804 (6.27 miles).

Friday, August 4: After I finish eating the Kakinoha-zushi for lunch, I get on the bus to explore some of the Nara temples on the outskirts of the main temples.

Kasuga Taisha Shrine lies in a wooded area southeast of the main temples of Nara.

sake barrels at entrance to Kasuga Taisha Shrine

Nara’s deer

Nara’s deer

The paths to the shrine are lined with lanterns, and thousands more are in the shrine itself.

gate to Kasuga Taisha Shrine

lanterns and deer on the pathway to Kasuga Taisha Shrine

stone lanterns on the path to Kasuga Taisha Shrine

stone lanterns on the path to Kasuga Taisha Shrine

stone lanterns

Kasuga Taisha Shrine is a Shinto shrine established in 768 and rebuilt several times over the centuries. It is the shrine of the Fujiwara family, a family of powerful regents in Japan. The Fujiwara dominated the Japanese politics of Heian period (794–1185) by marrying Fujiwara daughters to emperors. In this way, the Fujiwara gained influence over the next emperor who would, according to family tradition of that time, be raised in the household of his mother’s side and owe loyalty to his grandfather, according to Wikipedia: Fujiwara clan.

Kasuga Taisha Shrine

The origin of Kasuga Taisha Shrine dates back 1,300 years, when Takemikazuchi-no-mikoto, Japan’s most powerful deity, was invited to the sacred peak of Mt. Mikasa, a beautiful mountain behind this site, after the transfer of the national capital to what is now Nara City. The shrine grounds were completed in 768 with four altars for the deity already mentioned, plus a deity working for nation-building and a deity of wisdom and fortune-telling, as well as a Sun Goddess revered in the Middle Ages.

lanterns approaching Kasuga Taisha Shrine

The shrine has always received respect from citizens of Japan, even after the capital moved to Kyoto. Some 3,000 lanterns, stone or bronze, standing or hanging, were donated by worshipers since the Heian period in a show of their ardent faith.

Kasuga Taisha Shrine

lanterns at Kasuga Taisha Shrine

ema at Kasuga Taisha Shrine

lanterns at Kasuga Taisha Shrine

ema at Kasuga Taisha Shrine

Kasuga Taisha Shrine

lanterns at Kasuga Taisha Shrine

lanterns at Kasuga Taisha Shrine

lanterns at Kasuga Taisha Shrine

lanterns at Kasuga Taisha Shrine

There seems to be no end to the lanterns at Kasuga Taisha Shrine.

stone lanterns at Kasuga Taisha Shrine

Kasuga Taisha Shrine

lanterns at Kasuga Taisha Shrine

lanterns at Kasuga Taisha Shrine

lanterns at Kasuga Taisha Shrine

lanterns at Kasuga Taisha Shrine

Kasuga Taisha Shrine

lanterns at Kasuga Taisha Shrine

There is even a dark room with lit lanterns at the shrine.

lanterns at Kasuga Taisha Shrine

lanterns

lanterns

lanterns

lanterns

The ema at Kasuga Taisha Shrine show the lanterns and the deer encountered all along the way.

ema at Kasuga Taisha Shrine

With numerous rituals, the is a place of prayers for peace and prosperity for everyone on earth.

The Nagi (podocarpus nagi) pure forest in Kasuga Taisha was designated as a National Monument in 1923. It’s known for its spread of upright, dense evergreens with pointed, leathery, dark green leaves arranged on stiff, symmetrical branches. The tree works very well as a screen, hedge, strong accent plant, or framing tree.

Nagi (pure) forest in Kasuga Taisha

Wakamiya Jinja Shrine is an altar dedicated to the Deity of Wakamiya. The annual festival of Kasuga-Wakamiya-Onmatsuri has been held from December 15-18 continually since 1136. These religious rites, designated as Significant Intangible Folk Cultural Assets by the central government, include prayers for reducing the spread of epidemics or famines, as well as a gorgeous procession of people in traditional costumes.

Wakamiya Jinja Shrine

wishes at Wakamiya Jinja Shrine

Wakamiya Jinja Shrine

Wakamiya Jinja Shrine

Wakamiya Jinja Shrine

Nagi (pure) forest in Kasuga Taisha

ema at Wakamiya Jinja Shrine

ema at Wakamiya Jinja Shrine

Wakamiya Jinja Shrine is also surrounded by moss-covered stone lanterns.

moss-covered stone lanterns

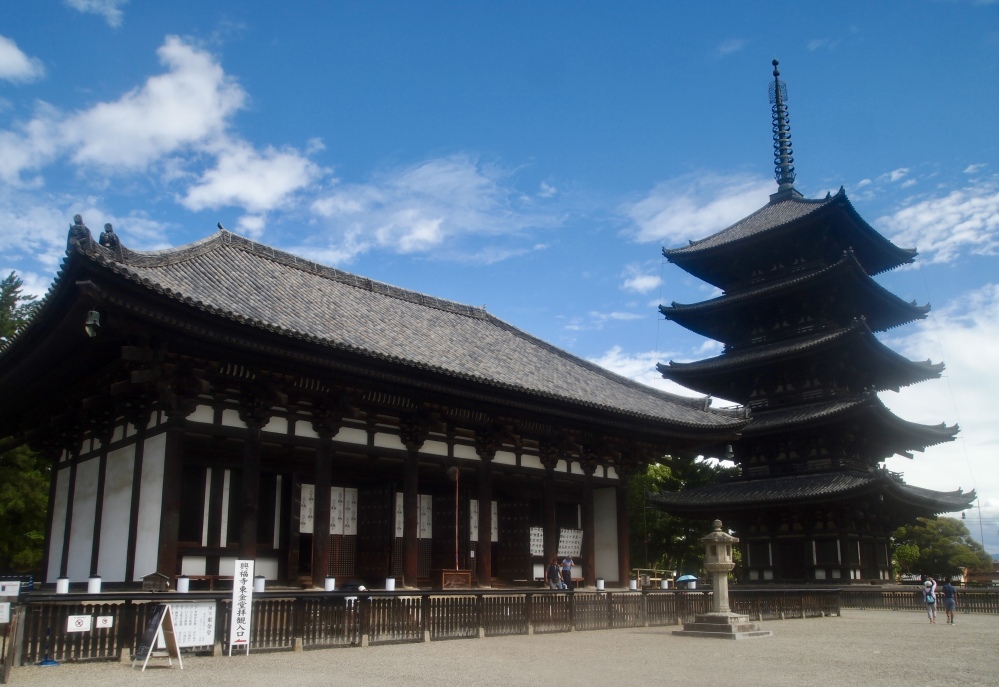

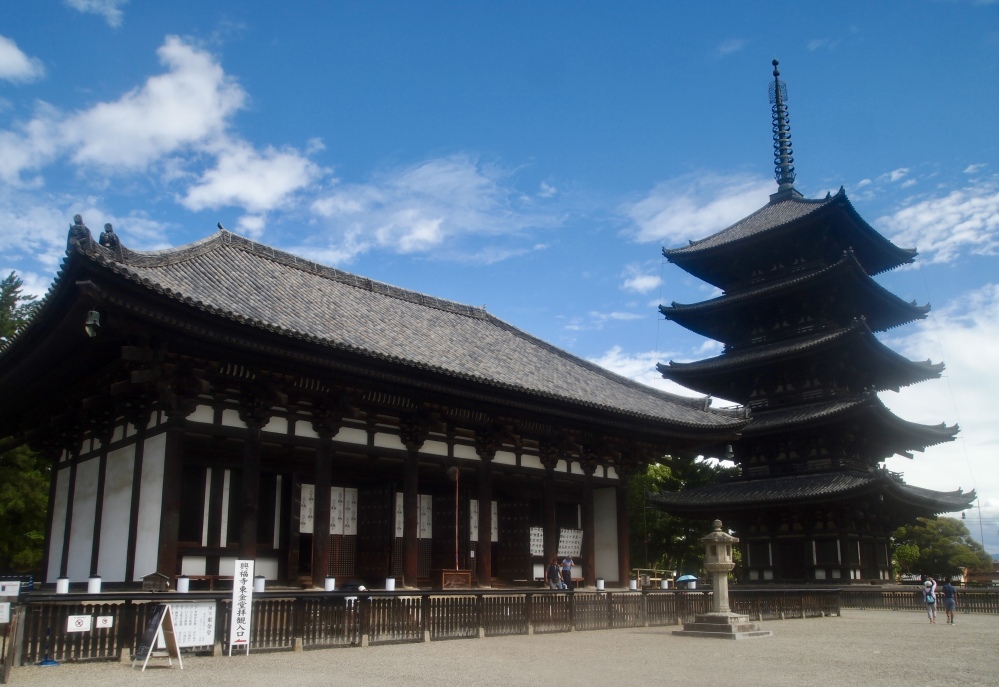

After visiting these two shrines, I take another bus to the famous Kohfukuji Temple. The original structure was built at the behest of the emperor Shōmu in 726 to speed the recovery of the ailing Empress Genshō.

This used to be the Fujiwara family temple. The temple was established in Nara at the same time as the capital was established here in 710. At the height of Fujiwara power, it is said the temple consisted of between 150 and 175 buildings. Fires and destruction as a result of power struggles have left only a dozen standing.

Today a couple of buildings of great historic value remain, including a five-story pagoda and a three-story pagoda.

Kohfukuji Temple

The “Eastern Golden Hall” or Tokondo, a 15th century building north of the Five-Story Pagoda, has a number of Buddhist statues including a large image of Yakushi Nyorai flanked by three Bodhisattva, the Four Heavenly Kings and the Twelve Heavenly Generals, plus a beautiful seated image of Yuima Koji (the Indian Buddhist sage Vimalakirti) (Japan Visitor). Sadly, no photography is allowed and I’m unable to find any postcards with the images.

Kohfukuji Temple

Kohfukuji Temple

At 50 meters, the five-story pagoda is Japan’s second tallest, just seven meters shorter than the five-story pagoda at Kyoto’s Toji Temple. Kofukuji’s pagoda is both a landmark and symbol of Nara. It was first built in 730. The pagoda had burnt down no less than five times before the 15th century. It was most recently rebuilt in 1426.

Five Story Pagoda at Kohfukuji Temple

The Three-Story Pagoda dates from the early 12th century and houses some important Buddhist paintings.

Three-story Pagoda

inside the Three-Story Pagoda

Five Story Pagoda

Kohfukuji Temple

Kohfukuji Temple

Kohfukuji Temple

deer art

Three-Story Pagoda

water pavilion at Kohfukuji Temple

ema at Kohfukuji Temple

water pavilion

Kohfukuji Temple

I use the bathroom on the grounds of Kohfukuji Temple, where I find these funny signs.

bathroom signs

bathroom signs at Kohfukuji Temple

After visiting Kohfukuji Temple, I make my way back through the congregations of deer on the way to my hotel.

Nara’s deer

Nara’s deer

Nara’s deer

I take a shower at the hotel before going out for dinner because I’m soaked in sweat. This heat and humidity in Japan is killing me!

downtown Nara

I head to Manna Indian Restaurant, luckily air-conditioned.

Menu for Manna Indian Restaurant

Manna Indian Restaurant

I enjoy Gobi Masala and a huge paan, accompanied by a cold beer.

Gobi Masala

I walk back under gorgeous skies to my hotel.

Nara at sunset

Nara at night

Nara

bicycles in Nara

signs in Nara

vendor in Nara

downtown Nara

the train station

heading to the train station

Back at the hotel, I have a 30-minute massage followed by a great night’s sleep. Tomorrow morning, I’ll head to Koyasan, which will be quite a convoluted trip.

Steps today: 18,075 (7.66 miles).

Friday, August 4: This morning, my second day in Nara, I take bus #70 for 20 minutes to two temples south of Nara proper: Toshodaiji Temple and Yakushiji Temple.

Toshodaiji Temple is the headquarters of the Ritsu Sect of Buddhism. It was established in 759 when the Chinese priest Ganjin Wajo (688 to 763), a high Buddhist priest of the Tang Dynasty, opened what was originally called Toritsushodai-ji Temple to help people learn the Buddhist precepts. He was invited by Japanese Buddhists studying in China to teach the Imperial Court about Buddhism. In 753, overcoming the hardship of losing his eyesight, he arrived in Japan during his sixth attempt to cross the ocean.

Toshodaiji Temple

The Kondo (Golden Hall or Main Hall) houses the principal seated Rushana Buddha, the standing Yakushi Tathagata statue and the standing Thousand Armed Avalokiteshwara National Treasure.

Kondo (Golden Hall or Main Hall) at Toshodaiji Temple

Thousand Armed Avalokiteshwara National Treasure

Photography isn’t allowed inside the halls, but below are three postcards of the Buddhas at Toshodaiji Temple. Click on any image for a full-sized slide show.

Thousand Armed Avalokiteshwara National Treasure

Rushana Buddha

Toshodai-ji

The Kondo, from the 8th century (Nara era) at Toshodaiji Temple is simple, but elegant, as are most Japanese temples.

Kondo (Golden Hall or Main Hall)

The Koro (Multi-storied building) from the 13th century (Kamakura era) is also called “Shariden (reliquary hall) because Buddha’s ashes brought by Ganjin Wajo were enshrined here. In the Zushi (miniature shrine) within the building, the Kinki (golden tortoise) is enshrined. This is also a National Treasure.

Toshodaiji Temple

The Rye-do (Chapel), from the 13th century, was originally the sleeping quarters for monks and is an important cultural property.

Rye-do (Chapel)

The Kodo (Lecture Hall) is from the Nara era. It is a building removed from the Heijo Palace and reconstructed, where the principal seated Maitreya Tathagata statue (important cultural property), the standing Jikoku-ten statue, and the standing Zojo-ten statue are enshrined. It’s another national treasure. I don’t have any pictures of these magnificent statues, sadly, as photography is not allowed.

Kodo (Lecture Hall)

Toshodaiji Temple

Toshodaiji Temple

Toshodaiji Temple

Toshodaiji Temple

A path leads through Toshodaiji Temple to another leafy path.

walkway at Toshodaiji Temple

It’s a welcome relief to find some shade on this hot and sultry day.

path at Toshodaiji Temple

At the end of the path, I find a lovely moss garden with dapples and shadows.

moss garden at Toshodaiji Temple

At the far end of the moss garden is the Kaizan Gubyo, or the Grave of Ganjin, the Founder of Toshodaiji Temple.

Grave of Ganjin, the Founder of Toshodaiji Temple

moss garden at Toshodaiji Temple

moss garden at Toshodaiji Temple

moss garden at Toshodaiji Temple

moss garden at Toshodaiji Temple

lantern at Toshodaiji Temple

moss garden at Toshodaiji Temple

moss garden at Toshodaiji Temple

Toshodaiji Temple is far from Nara proper and its crowds, so it is quite serene here.

Toshodaiji Temple

the Kondo of Toshodaiji Temple

On the way to the Kaidan (ordination platform), a garden of lotus blossoms beckons.

Toshodaiji Temple

gate to Kaidan (ordination platform)

Kaidan (ordination platform)

lotus at Toshodaiji Temple

lotus at Toshodaiji Temple

Toshodaiji Temple has a few beautiful lotus blossoms, even in the heat of the day.

lotus at Toshodaiji Temple

lotus at Toshodaiji Temple

bell at Toshodaiji Temple

Toshodaiji Temple

In looking at my map of these two temples, which are close to each other, I decide instead of taking the bus, I’ll walk to Yakushiji Temple. Though the map says it’s only a half kilometer, it seems longer than that, especially in this heat.

Yakushiji is the headquarters of the Hosso sect of Japanese Buddhism. The actual founder of the Hosso sect is Jion Daishi, but much of the Hosso Sect descends from the “Yugayuishiki” (Yogacara) teachings of Hsuan Tsang (600-664), a famous priest in the T’ang era in China. He studied Buddhism for 17 years in India. After returning to China, he translated 1,335 volumes of important Buddhist writings, and then taught them as well.

Yakushiji was planned around 680 by Emperor Temmu to pray for the recovery of his Empress from a serious illness. During the long construction period, Temmu died and his Empress acceded to the throne and was called Jito. The dedication ceremony for enshrining the chief Buddha, Yakushi Nyorai (the Buddha of Healing or Medicine Buddha) was held in 697. The entire compound was completed in 698 in the south part of Nara, in the Fujiwara Capital. Ten years later, the Capital was moved to the north of Nara (in 710) and Yakushiji was moved to its present site in 718. It is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Yakushiji Temple

Yakushiji was burnt down and destroyed by fires, wars, or natural disasters several times. The most damage was caused by the civil war in 1528. Today only the Yakushiji Triad in the Kondo, the Sho-Kannon in the Toindo and the East Pagoda recall the grandeur of its original features.

Today, sadly, some major parts of the compound are under construction.

Kodo, or Great Lecture Hall, at Yakushiji Temple

Kondo, or Golden Hall, at Yakushiji Temple

Sadly, because no photography is allowed of the famous Buddha statues, I purchase a couple of postcards of the images. Neither the postcards, nor any photos, could do them justice, as they are imposing and sit within the beautiful Kondo, or Golden Hall. Between the Buddha statues at Toshodaiji Temple and here, at Yakushiji Temple, I’m in awe. These are truly magnificent pieces of art.

Postcards from Yakushiji Temple show the famous Yakushi Triad: the Yakushi Nyorai flanked by the Bodhisattvas of the sun and moon. These are arguably some of the most beautiful statues in all of Japan.

The postcard on the left shows Yakushi Nyorai, a bronze statue (225 cm, or 7.4 feet tall) that is a National Treasure from the Hakuho Period (645-710); he is the Buddha of Healing and the Lord of the Emerald Pure Land in the East, who vowed to cure diseases of the mind and body. He was already popular in Japan before the 7th century. He is also worshiped in order to achieve longevity. Though Yakushi Nyorai usually has a medicine pot in his left hand, this one does not.

The postcard to the right shows one of two Bodhisattvas – Nikko Bosatsu, who attends Yakushi Nyorai on the right side. Gakko Bosatsu (not pictured), stands on the left side. Both are about 320 cm, or 10.5 feet tall. Nikko means the sunlight and Gakko means the moonlight. They are impressive because of their twisted bodies, their graceful features, and the free flow of their robes.

Yakushi Nyorai is similar to the doctor of mind and body and Nikko and Gakko Bosatsu are the nurses.

Yakushi Nyorai

Nikko Bosatsu (National Treasure) – Yakushiji Temple

“Pagoda” means grave in Pali, the ancient Indian language, and it was called “stupa” in Sanskrit. Pagoda means the grave of Buddha. Yakushiji is the first temple that had twin pagodas on its grounds.

Unfortunately, the original West Pagoda at Yakushiji Temple was burned down in 1528. After the reconstruction of the Kondo, the West Pagoda was rebuilt in 1980. The East Pagoda (not pictured), which miraculously survived the fire that destroyed Yakushiji in 1528, is the only surviving architecture of the Hakuho Period in Japan. Unfortunately for me, the East Pagoda is under renovation and is covered in scaffolding today.

West Pagoda at Yakushiji Temple

Buddha image at Yakushiji Temple

West Pagoda at Yakushiji Temple

Golden Hall at Yakushiji Temple

The Middle Gate stands between the South Gate and the Kondo, or Golden Hall. You can see a hot wind is blowing.

Middle Gate at Yakushiji Temple

Guardian of the Middle Gate

Guardian of the Middle Gate

The Golden Hall at Yakushiji Temple is truly magnificent, especially with those spectacular Buddha statues inside.

Golden Hall at Yakushiji Temple

West Pagoda

Buddha at Yakushiji Temple

After my visit to both of these fabulous temples and their resplendent Buddha images, I catch bus #70 to return to Nara. Back at the train and bus station, I search inside a big supermarket for kakinoha-zushi, which translates as “persimmon leaf sushi.” The Nara region is famous for this delicacy. I am able to show the name in Japanese to one of the supermarket employees, who points out the package.

Kakinoha is individual pieces of sushi wrapped in persimmon leaf, shown below. You’re not supposed to eat the persimmon leaves. I sit outside on the front stoop of the supermarket with a bunch of other people enjoying this treat, although it’s a little awkward opening up the persimmon leaves and eating them while holding them on my lap.

kaki-no-ha

kaki-no-ha

kaki-no-ha

After I finish eating, I’m on my way by another bus to Kasuga Taisha Shrine, Wakamiya Jinja Shrine, and Kofuku-ji. 🙂

Thursday, August 3: This morning, I take the 10:17 a.m. Shinkansen from Hiroshima to Kyoto, arriving at 11:54 a.m. There, I get on the Nara Line to Nara Station (12:03-12:48). On the train, I sit beside a 34-year-old guy named Zachary who teaches grammar and literature to middle school students at a private school in L.A. He’s going to Nagasaki to make some kind of presentation for the peace ceremony on August 9. We chat for the entire 45 minutes; in Nara, I disembark from the train and am off to find the Hotel Nikko Nara.

After dropping my bags at my hotel, which is a nice one right next to the train station, I stop to eat tempura and rice at a restaurant at the station. There I meet a friendly and talkative Japanese housewife named Hiromi who asks if she can join me. She tells me she’s from Yokohama and has come down here for one day to see two things, one museum in Kyoto and one in Nara. She plans to return home late tonight. She herself has no children but she asks endless questions about my teaching job and says she is embarrassed on behalf of all Japanese people for my misbehaving “I” class.

After lunch, I hop on Bus #2 at Nara Station and I hear a loud: “Cathy!!” I look around to find Christine from Luxembourg, who I met in Nikko last weekend. When we talked about our travel plans in Nikko, I knew that the only place we might intersect was in Nara, but never in a million years did I actually expect to run into her here. What a small world it is sometimes!

She is on her way to Yoshiki-en, a garden that is free for foreign tourists. I am on my way to the Great Buddha, but as the garden is on my way, we explore the garden together. It is sweltering and humid, but we wander around, enjoying the shade offered by little pavilions along the way. There are three unique gardens within Yoshiki-en: a Pond Garden, a Moss Garden and a Tea Ceremony Garden. The Moss Garden has a detached thatch-roof tea house. In the Pond Garden, slopes and curves of the land remaining from the Edo period (17th-19th centuries) blend with the buildings. The garden is a suitable environment for hair moss (Polytrichum), so the whole area is covered with it. The garden, originally the home of the high priest of Tōdai-ji, was laid out in 1918.

Yoshiki-en

Yoshiki-en

Yoshiki-en

Yoshiki-en

Click on any of the pictures in the gallery below for a full-sized slide show.

Yoshiki-en

Yoshiki-en

tea house at Yoshiki-en

tea house at Yoshiki-en

Yoshiki-en

Yoshiki-en

Yoshiki-en

After we explore the garden, I say goodbye to Christine and make my way to Tōdai-ji, walking through Nara-kōen, a park that is home to about 1,200 deer. The deer are considered National Treasures. In pre-Buddhist times, they were considered messengers of the gods. The deer roam freely throughout the park and won’t hesitate to approach people if they think they can abscond with a few morsels of food.

Nara’s deer

Tōdai-ji, “Great Eastern Temple,” was founded in 728 as a resting place for the Crown Prince Motoi, son of Emperor Shōmu (r. 724-749). The temple was used as the head temple of all provincial Buddhist temples of Japan and grew so powerful that the capital was moved from Nara to Nagaoka in 784 in order to lessen the temple’s influence on government affairs (japan-guide.com: Todai-ji Temple). It is believed the temple was built to consolidate the country and serve as its spiritual focus, but its construction almost brought the country to bankruptcy, according to Lonely Planet Japan.

The temple is famous today for housing the famous Daibutsu (Great Buddha) in the Daibutsu-den Hall of the temple.

I first pass through an outer gate.

approaching Todai-ji

Once through this outer gate, I’m face to face with the world’s largest wooden building, Daibutsu-den Hall. Unbelievably, this structure, rebuilt in 1709, is only two-thirds the size of the original.

Todai-ji

Todai-ji

Todai-ji

Todai-ji

Todai-ji

The Daibutsu (Great Buddha) inside, originally cast in 746, is one of the largest bronze sculptures in the world. At one time it was covered in gold leaf, quite an impressive sight for Japanese 8th century visitors. The present statue, recast in the Edo period (1603 – 1868), stands 15 meters tall; the seated Buddha represents Vairocana, the cosmic Buddha believed to give rise to all worlds and their respective Buddhas (Lonely Planet Japan), and is flanked by two Bodhisattvas.

Daibutsu

Daibutsu

The Kokuzo Bosatsu, seated to the left of the Daibutsu, is the Bodhisattva of memory and wisdom. Students pray to him for help in their studies, while the faithful pray for enlightenment. Standing to the left of the Daibutsu and the Kokuzo Bosatsu is Komokuten, a guardian of the Buddha. He stands upon a demon (jaki), which symbolizes ignorance, and holds a brush and scroll, which symbolizes wisdom (Lonely Planet Japan).

Daibutsu

Daibutsu

Kokuzo Bosatsu

Komokuten

A pillar with a hole in its base is supposedly the same size as the Daibutsu’s nostril. It is said that those who can squeeze through this opening will be granted enlightenment in their next life (japan-guide.com: Todai-ji Temple). I watch as a boy squeezes through the hole. I guess he will have guaranteed enlightenment!

Hole in Pillar

Hole in Pillar

Hole in Pillar

I always love to check out the ema at every temple, and I find this cute one at Tōdai-ji: “I wish my family won’t be angry at Matthias. Hooray.”

Ema at Todai-ji

Ema at Todai-ji

Seated to the right of the Daibutsu is Nyoirin Kannon, one of the Bodhisattva that preside over the six realms of karmic rebirth.

Nyoirin Kannon

Nyoirin Kannon

Daibutsu

Pindola was one of the sixteen arahats, who were disciples of the Buddha. Pindola is said to have excelled in the mastery of occult powers. It is commonly believed in Japan that when a person rubs a part of the image of Binzuru (Pindola Bharadvaja) and then rubs the corresponding part of his own body, his ailment there will disappear.

Binzuru

The Tōdai-ji grounds are quite verdant at this time of year.

Todai-ji grounds

Todai-ji grounds

Todai-ji grounds

Nigatsu-dō lies to the east of the Great Buddha Hall and up the side of Mount Wakakusa. Nigatsu-dō (which translates to “The Hall of the Second Month”) is a beautiful hall that overlooks the city of Nara and provides a view of its ancient structures. To get to it, I walk through peaceful neighborhoods lined with lanterns, a welcome relief after the crowds at Tōdai-ji.

walking to Nigatsu-dō

walking to Nigatsu-dō

inside cafe at Nigatsu-dō

doors at Nigatsu-dō

I line up with other visitors along Nigatsu-dō’s balcony to absorb the views.

Nigatsu-dō

view of Nara from Nigatsu-dō

The original construction of Nigatsu-dō hall is estimated to have completed somewhere between 756 and 772. Nigatsu-dō was destroyed in 1667 due to a fire. Re-construction of Nigatsu-dō was completed in 1669. In 1944, it was chosen by Japan as one of the most important cultural assets of the country. This sub-temple of Tōdai-ji reminds me of Kiyomizu-dera, which I visited in Kyoto in 2011 (golden pavilions, rock gardens, bamboo groves, and white-gloved train conductors).

roof at Nigatsu-dō

lanterns at Nigatsu-dō

view from Nigatsu-dō

lanterns at Nigatsu-dō

view from Nigatsu-dō

lanterns at Nigatsu-dō

I love all the lanterns at Nigatsu-dō.

Nigatsu-dō

Nigatsu-dō

Nigatsu-dō

Nigatsu-dō

ema at Nigatsu-dō

ema at Nigatsu-dō

Nigatsu-dō is quite majestic sitting high on the hill.

Nigatsu-dō

steps to Nigatsu-dō

Nigatsu-dō

shrine at Nigatsu-dō

Nigatsu-dō

Nigatsu-dō

Nigatsu-dō

Nigatsu-dō

Nigatsu-dō is best known for Omizutori, a fire and water ceremony on March 12 every year, where huge flaming torches are held out from the temple balcony. The next day, sacred water is drawn from a well under the temple, which is said to have healing properties. The ceremony has been held here without a break since the temple’s founding in 752 (Visit Nara: Nigatsu-do).

Nigatsu-dō

Sangatsu-do Hall is home to a small collection of Nara-period statues.

Sangatsu-do Hall

Sangatsu-do Hall

Tamukeyama Hachimangu is a Hachiman shrine, dedicated to the kami Hachiman, a divinity of archery and war. It was established in 749. Kami, spirits or phenomenon worshiped in the Shinto religion, enshrined here include: Emperor Ōjin, the 15th emperor of Japan; Emperor Nintoku, the 16th emperor; Empress consort Jingū, who ruled beginning in the year 201; and Emperor Chūai, the 14th emperor.

Tamukeyama Hachimangu

Tamukeyama Hachimangu

ema at Tamukeyama Hachimangu

ema at Tamukeyama Hachimangu

Tamukeyama Hachimangu

Tamukeyama Hachimangu

ema at Tamukeyama Hachimangu

Tamukeyama Hachimangu

ema at Tamukeyama Hachimangu

Tamukeyama Hachimangu

Tamukeyama Hachimangu

After leaving Tamukeyama Hachimangu, I make my way back to Tōdai-ji, passing a spiral sōrin, circling Kagami-ike Pond, and finally walking under Nandaimon Gate. Nara’s deer keep me company the whole way.

sōrin at Tōdai-ji

Kagami-ike Pond

Kagami-ike Pond

Kagami-ike Pond

deer of Nara

As I’m leaving Tōdai-ji, I walk through the Nandaimon Gate, a large wooden gate, rebuilt in the 13th century, watched over by two fierce-looking statues. Representing the Nio Guardian Kings, the statues are designated national treasures together with the gate itself.

Nandaimon Gate

Nandaimon Gate

deer of Nara

deer of Nara

Nandaimon Gate is impressive in its size and ancient grandeur.

Nandaimon Gate

The deer of Nara are everywhere!

deer in Nara

Nara’s deer

deer

deer in Nara

deer in Nara

deer in Nara

Nara’s deer are having a rest near the main gate, undoubtedly perspiring in this sizzling weather.

Nara’s deer

After taking a shower back at my hotel, I go into Nara Proper to have a Pizza Margherita at the Mellow Cafe.

mellow cafe

On the way back to my hotel, I stop for an ice cream with a little deer on top. It provides a bit of welcome relief from the heat

pizza at mellow cafe

me with ice cream in Nara

Tomorrow, I’ll explore more of Nara.

Steps today: 15,835 (6.71 miles)

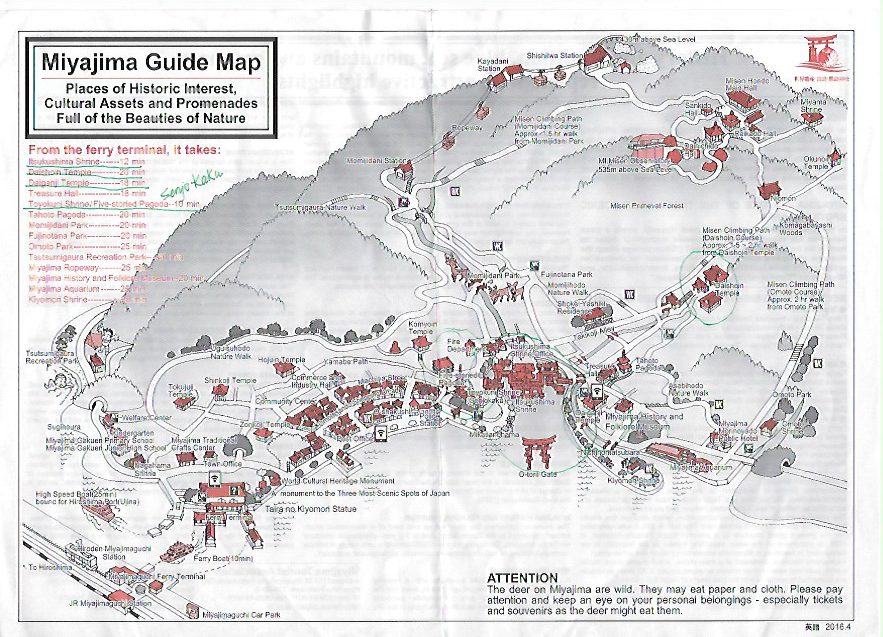

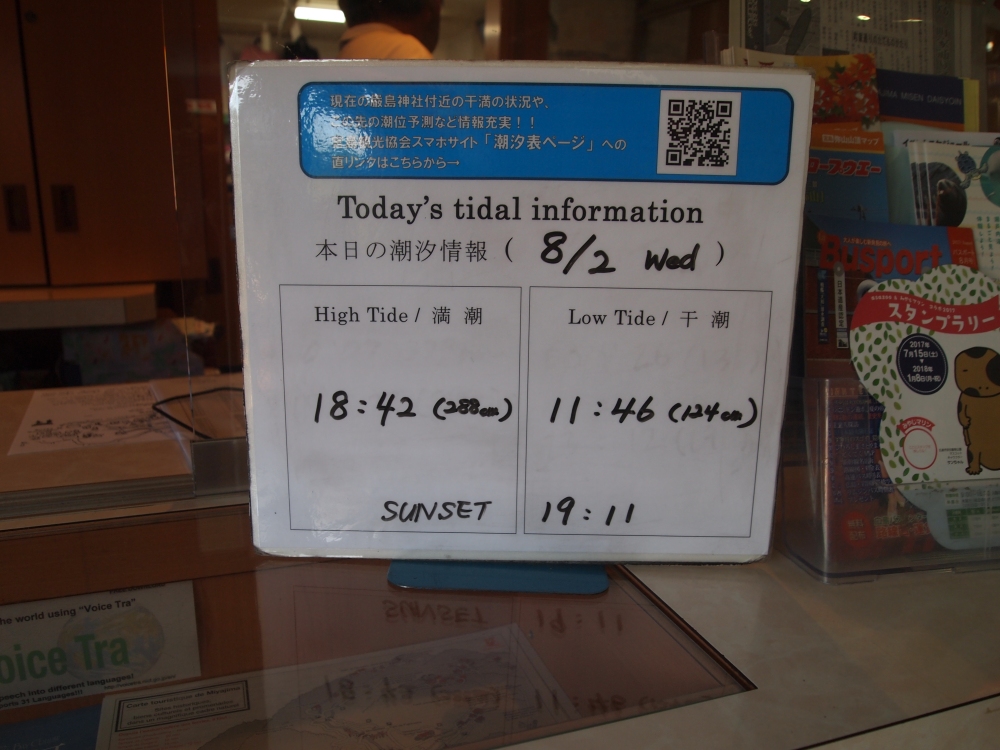

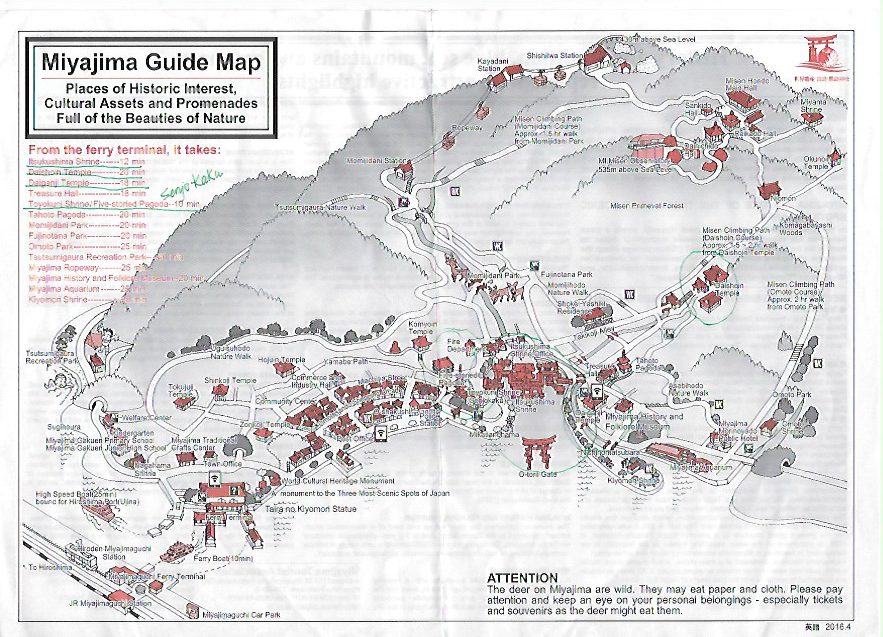

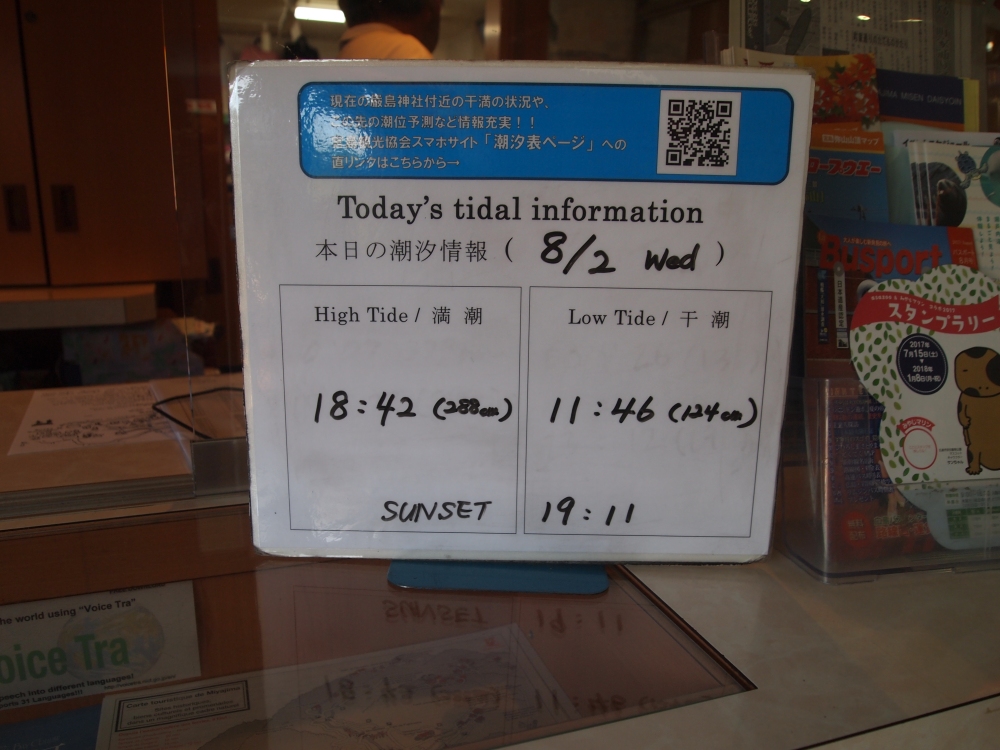

Wednesday, August 2: After visiting the O-torii Gate at Itsukushima Shinto Shrine at somewhat low tide, I take a break to walk uphill toward Daishō-in, a historic Japanese temple complex on Mount Misen, the holy mountain on Miyajima. Including Mt. Misen, Daishō-in is within the World Heritage area of Itsukushima Shrine.

Mt. Misen sits in the middle of Miyajima Island. The mountain was opened as an ascetic holy mountain site by Kobo Daishi in the autumn of 806 when he underwent ascetic practice for 100 days in the mountain. The fire lit by Kobo Daishi is said to have been burning for 1200 years. The fire was used to light the Flame of Peace in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

Daishō-in Temple is one of the most prestigious Shingon Temples in the western part of Japan. The Shingon, or “True Word,” branch of esoteric Buddhism, was introduced to Japan from China in the 9th century. Shingon involves trying to reach the eternal wisdom of the Buddha that wasn’t expressed in his public teaching. The sect believes that this wisdom may be realized through rituals using body, speech, and mind, such as the use of symbolic gestures (mudras), mystical syllables (dharani), and mental concentration (yoga). The whole is intended to arouse a sense of the pervading spiritual presence of the Buddha that resides in all living things, according to Encyclopedia Britannica: Shingon.

In the 12th century, Emperor Toba founded his prayer hall in Daishō-in. The temple had close links with the Imperial Family until the 19th century. Emperor Meiji stayed in the temple in 1885 (Welcome to Miyajima: Daishō-in).

Though I love the bright vermilion of many Japanese temples, I have a fondness for the wooden structures that look ancient and weathered and seem to blend in with nature.

The Niomon Gate serves as the official gateway into the temple. A pair of guardian king statues stand by the gate. Nio kings are believed to ward off evil, and are determined to preserve Buddhist philosophy on earth.

Niomon Gate of Daishō-in

Kukai, posthumously known as Kobo Daishi, is the founder of the Shingon sect. In 804, at age 31, he went to Tang, China, where he mastered profound esoteric teachings. He is also well-known as one of the three greatest calligraphers in Japan.

Niomon Gate

lantern at Daishō-in

Lining the steps to the temple are the statues of 500 Rakan statues. These represent Shaka Nyorai’s disciples. These images all have unique facial expressions. Besides the Rakan statues listed on the map below, there are other statues spread sporadically throughout the temple complex.

map of Rakan statues at Daishō-in

Rakan statues at Daishō-in

Rakan statues at Daishō-in

Rakan statues at Daishō-in

Rakan statues at Daishō-in

Rakan statues at Daishō-in

Rakan statues at Daishō-in

Rakan statues at Daishō-in

Rakan statues at Daishō-in

Rakan statues at Daishō-in

Rakan statues at Daishō-in

Rakan statues at Daishō-in

Rakan statues at Daishō-in

Rakan statues at Daishō-in

Rakan statues at Daishō-in

Rakan statues at Daishō-in

There are so many interesting things to see at this temple complex, even if I don’t know what many of them are.

water pavilion at Daishō-in

Daishō-in

Shimo Daishi-do Hall at Daishō-in

Along the temple steps is a row of spinning metal wheels that are inscribed with sutra (Buddhist scriptures). Turning the inscriptions as one walks up is believed to have the same effect as reading them. So, without any knowledge of Japanese, a visitor can be blessed with enormous fortune by turning the wheels (japan-guide.com: Daishō-in).

stairs and prayer wheels

The bell in the belfry was once rung to tell the time in the morning, afternoon and evening in the past. Now it is rung to start the time for worship.

Belfry

Kannon-do Hall was established to enshrine the image of Kannon Bosatsu, the Deity of Mercy.

Kannon-do Hall

Kannon-do Hall

ceiling at Kannon-do Hall

treasures in Kannon-do Hall

treasures in Kannon-do Hall

A mandala using colored sand depicts the divine figure of Kannon Bosatsu, the symbol of mercy. The mandala was made by Buddhist priests from Tibet.